A Flyer for “A Flyer for Flight”

July 4, 2015

Accompanying text

by Normand Renaud

Imagine that one day in all public parks, we’ll see people performing a variety of elegant movements in order to develop the capacity to fly using nothing more than the will to fly, with no apparatus whatsoever. L’art de s’envoler / A Flyer for Flight by Maryse Arseneault, an installation exhibited in Sudbury at the Galerie du Nouvel-Ontario in June 2015, was made up of several components, but that scene best struck my imagination, even though I didn’t witness it. (However, such a moment did take place during the artist’s stay.) All of the work’s components stem from the same intention: to make aspiring to a superhuman capability a familiar, popular and commonplace goal and to incite us to undertake a patient and determined effort to achieve it.

The title of the work includes a pertinent play on words: the “flyer” in question is in fact a little leaflet which extends an invitation to practice l’art de s’envoler, the art of flight. The work’s other components provide glimpses of such practices. Technology and science have nothing to do with the artist’s proposition; rather, it is through meditative exploration nourished by firm belief that the impossible will be achieved. Nowadays, aeronautics is highly evolved and daredevils wearing nothing more than wingsuits accomplish hair-raising feats of flight. However, Maryse Arseneault champions other means: we could one day learn to fly without the use of prosthetics, by using the mind to penetrate the mysteries of our relationship with matter.

“To fathom something is to be ready to perceive it.” That sentence is another detail in the work that struck a chord for me. It is heard in what appears to be the main component of the work upon entering the gallery. Two videos are projected on facing walls. On one side, an instructor performs a series of movements while explaining their meaning. On the other side, a small group of people follow her instructions. One notices a slightly unusual detail: the participants wear aprons, perhaps to convey the skills and professional attitude the practice requires. The spectator stands between both video images and would simply need to perform the movements to be engaged in the process. The invitation is discrete, yet clearly felt.

At first glance, this “art of flight” seems somewhat similar to tai chi. Simple instructions describe a sequence of movements to be executed while absorbing their significance for the quest of flight. Each movement is associated with an element: earth, air, water, wood, fire and metal. For example: “The next element is water. Arms aligned with ears like whiskers. This will be useful for listening. (…) After a few rounds, you will feel a tingling sensation at your fingertips. That is the world outside of yourself that you are waking up to.” Similarly, each of the six elements is associated with a meditative posture and its relationship with flight is briefly explained.

The narration of the lesson begins with a personal confession. Here is an excerpt. “Later in my youth, I learned to control my dreams, especially those where I was learning to fly. To battle my weightlessness, I had to understand how to place the weight of my body with fuller awareness. That way, I could avoid flying away into empty space.” The process of this art of flight is therefore rooted in the intimacy of the artist’s childhood fears and it shares the sense of reality inherent in dreams.

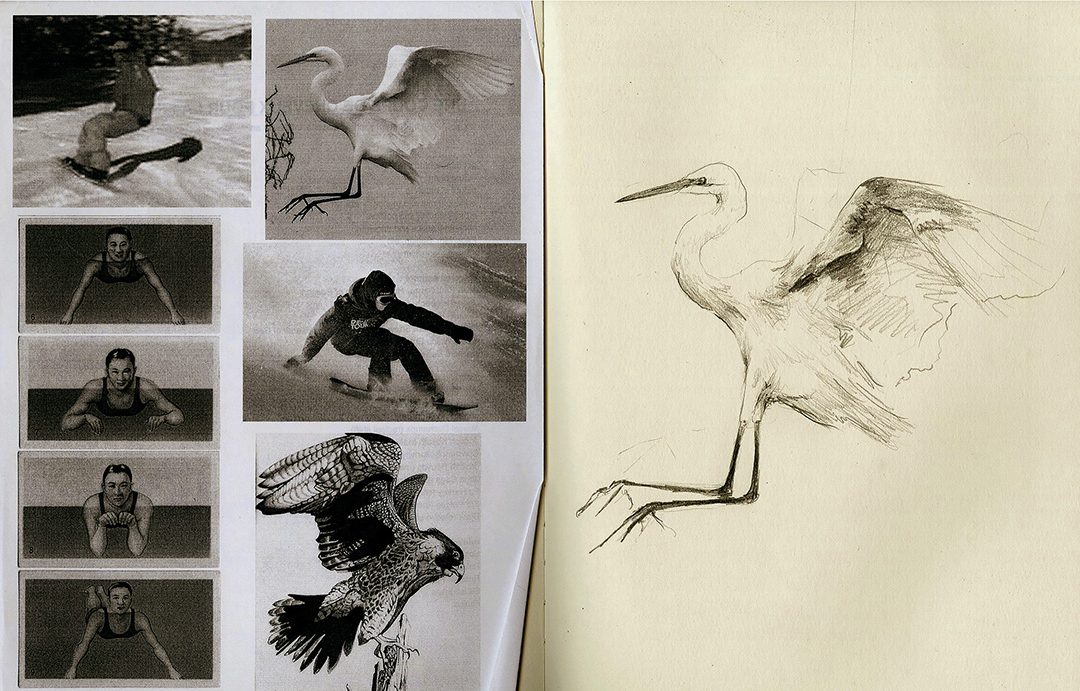

Another of the work’s components consists of a series of drawings of flying and diving figures – aquatic birds, marine mammals, human swimmers –, each of which is also associated to the various elements. These drawings are executed with painstaking precision and realism. One senses the tension of attention, the artist’s careful observation of minute details in these true incarnations of the will to fly.

A final component of the work is especially interactive. It invites the spectator to experience, perhaps as a moment of illumination, the object of the meditative process. A small trampoline is connected by wires to an obsolete piece of equipment: a videocassette player connected to a cathode ray television set. By bouncing on the trampoline, the spectator sometimes manages to activate a function such as fast forward, rewind or play, but with limited precision. The rudimentary quality of this apparatus elicits a smile in our era where virtual reality equipment can provide the sensation of interacting with an imaginary 3-D environment. Nonetheless, the experience produced here is that of a body clumsily, yet successfully, transforming its immediate environment simply through it conscious and active presence.

L’art de s’envoler / A Flyer for Flight presents itself as an act of faith in the possibility of transforming humankind’s relationship with matter and thereby breaking through the limits of what is possible. In the times of mythic Icarus or the drawings of Da Vinci, the dream of flight seemed chimerical, but the will to fly ultimately triumphed. We acquired the capacity to fly by harnessing the forces of physics through technological progress. Where would we be today if the same determined force of will had been devoted just as resolutely to exploring the powers of art and mind? Would humankind have harnessed other more obscure, yet no less real forces? This art of flight aims to open the way for the emergence of a fuller awareness of the human presence in the vast web of ecological and cosmic forces, as represented in the work by the six elements and their effects on mind and spirit. Throughout the centuries, abundant and powerful energies have been invested in the expansion of spiritual consciousness, not without effect. The new and seductive horizon in this artist’s proposition is its suggestion to concentrate these energies on a more narrowly defined goal: flight.

Such is the avenue of reflection pursued in Maryse Arseneault’s installation. Its aim is to awaken an intuition similar to what might have driven the first marine creatures that dragged themselves onto land and learned to drawn in oxygen from air instead of water. We are meant to realize that evolution is preceded and prepared by desire, and to act accordingly. “To fathom something is to be ready to perceive it.” In this vision of our species’ evolution, humans no longer invest in their ability to control matter. Rather, the aim is to become aware of unknown relations between matter and our bodies and minds. We should cease to objectify matter, in order to become aware of our intimate attachment and equality with matter. Thereby, we would be more totally human. And we could fly.

For the time being in our evolution, the prophetic desire for free flight takes form in a kinetic sculpture made of human bodies in a public park. It’s a scene that makes you smile. Then, it makes you dream.