Foire d'art alternatif de Sudbury (Alternative Art Fair of Sudbury)

For its sixth edition, the FAAS will take place at The Village on Mackenzie, the former St-Louis-de-Gonzague elementary school. From the basement to the second floor, the artists will share the numerous rooms offered by the historic building to explore their ideas about territory. Intimate or dreamed places, shared territories, changing borders, immigration, relationship to the environment and imaginary maps are some of the many ways to perceive the topic in which individual and collective considerations mingle.

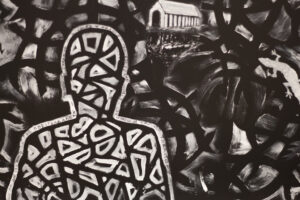

Installation, Debajehmujig, 2018.

Introduction

Back to School

Danielle calls out at every opportunity: “Come see us! We’re opening Thursday at Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague; you know, the old school across from Sudbury Secondary!” We’re excited… A childlike joy in (re)discovering a place devoid of occupants, a space filled with memories, right there, so near and so visible on Mackenzie Street, yet inaccessible. A playground. A chance to come together.

Citizens are invited to drop in and see what is coming into existence. To witness the great care put into constructing installations and designing performances. To get involved, have their portrait done, comment on their relationship with the city, respond to calls for help: would you happen to have…? The FAAS represents a dual opportunity: for the public, to be immersed in the act of creation and gain an understanding of the processes involved; and for the artists, to work in a novel context and experiment with new parameters. It’s a networking opportunity as well, like lines drawn between stars form constellations, trace meanings.

The FAAS is a community affair and the community has answered the call. First to come are students from nearby schools. At the front door of the former elementary school, they are greeted by Professor Gustave Erronéous Morbeus. He has arrived with his vehicle, his paraphernalia and his eagerness to interact with Sudbury, its citizens, its places. For several years, André Martel, a performance artist invited by Voix Visuelle, has donned the steampunk-inspired costume of the character he created as his entryway to Otherness. Serving as actor as well as prop in his performances, he makes himself available to bystanders attracted by his offbeat look, which evokes both the early industrial era and the age of space travel. How will young people react? Questions fly out in both directions, contact is established. Soon, teenagers are taking turns climbing onto a tandem bicycle powered by an electric motor and are off for jaunts through downtown streets with the artist. Who is leading whom? Who is performing, who is attending? This interaction is an opportunity to reflect on public space and what it represents. The artist, who hails from the eastern part of the province, sees things differently than local inhabitants who are familiar with the area. Perched on their vehicle, the artist and his guest don’t pass unnoticed and elicit smiles from motorists. For anyone who is willing to perform with Martel, a familiar street a thousand times travelled becomes a stage.

The artist spends the following days wandering around the neighbourhood with a bird cage on his head and sundry items at hand, offering passers-by a moment of pleasant peculiarity. Whether in a shopping centre or a library, interaction with the space and its users is central to Martel’s incursions. He finds his place in a setting, even when he seems out of place: he strikes a pose, talks to passers-by, answers their questions. In this, the festival’s first performance, art is not consigned to a dedicated space, but spills over into other spaces, introducing an element of surprise into everyday life. The places where we go to shop, attend a meeting or browse books become anchor points for memories of unexpected experiences. Martel’s spectators did not come to the FAAS; rather, the FAAS came to them, in places of their choosing which henceforth will subjectively bear the trace of an improbable encounter that happened there one chilly October day.

The Galerie du Nouvel-Ontario’s programming committee had decided that the event would explore the topic of territories and how they are shared. Specifically: how can we welcome newcomers to a territory that we do not own? Remember that in 2018, the migrant crisis in Europe, which had already been front page news for several years, was aggravated by the civil war in Syria and the response of European nations that turned away refugees and absolved themselves of responsibility for the rising death count at their doorstep. There was also the war and famine in Yemen, the genocide of the Rohingyas and, in America, the raising of a wall on the border between Mexico and the United States, among other developments. “Build that wall!” urged Trump, as if hiding the misery of others were enough to resolve stark inequalities on the American continent that stem from centuries of imperialistic policy.

Reflecting on territory necessarily involves the environment. Also in 2018, Greta Thunberg began her Fridays for Future strike in front of Sweden’s parliament buildings. The state of the territory we inhabit, its conservation, its capacity to harbour and regenerate life, are core questions for this young environmental activist and, alongside her, an entire generation that has introduced the new concept of “ecoanxiety” into everyday speech. Territory is about more than just being somewhere; it’s also about being able to live there and handing down a home for future generations. That is becoming less and less likely as the climate changes, dragging down biodiversity, the agricultural potential of lands, the livability of shores and the bounty of oceans. It’s enough to keep you awake at night.

In June of that same year of 2018, Sudbury was the scene of hearings before the Ontario Superior Court of Justice in a landmark lawsuit brought against the federal and provincial governments by the twenty-three First Nations signatories to the Robinson-Huron and Robinson-Superior treaties. Recorded and aired live on social media – a first – the hearings exposed the iniquity of treaty payments that have not been indexed to inflation since the treaties were signed… in 1850. For the first time, the underside of these treaties was exposed, explained and analyzed in wide public view. As the FAAS was opening, we awaited Justice Patricia Hennessy’s decision, which would determine if governments had truly upheld the spirit of its treaty commitments. We were both hopeful and fearful: would the outcome of this lawsuit bring at least a modicum of recognition of the harms that colonization inflicted on indigenous people? Months later, the judge would rule in favour of the First Nations, but the Government of Ontario appealed, and as these lines are being written, the judicial process had not yet concluded.

Now, back to our initial question: how to welcome immigrants, climate refugees or political refugees while respecting a territory that does not belong to us, where we ourselves are no more than guests? Art has the potential to create a neutral ground where conversation is possible. By adopting À qui? (To whom?) as the theme statement for the sixth edition of the FAAS, the GNO’s intention was to welcome this conversation, to face difficult realities and most of all, to reaffirm the potential of art as a vector for world change.

With thirty-six Canadian and international artists taking part, FAAS 6 was shaping up to be the festival’s biggest edition ever. We needed a sufficiently large venue, sheltered from the elements (the fair being held at the end of October), which could provide good conditions for all of these artists’ creative work. Confirmation that we would have access to Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague was slow in coming, which reduced our room for manoeuvre and held up planning for the biennial event. Meanwhile, the sky was falling on our heads (almost literally): after months of anxious glances at the gallery’s ceiling through which water was seeping, we learned that finally the building’s roof would be rebuilt… two months before the FAAS. So, the team was suddenly expelled from its headquarters for a six-week exile and everything became that much more complicated. The need to find a space to meet and work together to organize the festival was especially urgent because we were about to welcome Jérôme Havre as an artist-in-residence in our gallery space, in preparation for the exhibition entitled “Intérieur.” Plus, there was a grant request to prepare, with a deadline coinciding with the opening day of the FAAS.

The months leading up to the festival were stressful in every way, but we pressed on towards the FAAS like runners to a finish line. We looked forward to meeting the artists, discovering their works, formulating the questions in our minds, hearing their points of view. For this festival, like all of the earlier editions, our goal was to make people see Sudbury in a new light, thanks to the in-situ creative process. What would these artists from far and near make us realize about the places we inhabit? But also, are we the only ones who no longer know where we are, who recognize their privileges but don’t know how to transpose awareness of inequality into durable concrete actions?

We believed (naively) that bringing together artists with a very wide variety of backgrounds would be enough to foster dialogue. We believed (again, naively) that if we opened up a creative space, everyone would be able to find their place and easily make their voices heard. We hoped that all of the different points of view would be embodied in the creative works, but also expressed at the round table discussion featuring four artists from different communities (Immigrant, Franco-Ontarian, LGBTQ, Indigenous) with simultaneous French to English translation. Many participants appreciated that the festival’s activities attempted to bring perspective to our relationship with territory at a time when that subject is sensitive and in a context where could easily have been set aside. However, as we would learn, the parameters we had put in place stemmed from a White, colonized understanding of what creating is, and that implicitly affects the expected outcomes. At the round table, we were criticized for not having made enough effort to involve local indigenous leaders and artists in designing the architecture of the FAAS; for imposing a framework that did not recognize their deep and sensitive connection to the question; for not showcasing more than the diversity of identities, but also the diversity of ways of doing. “This is not a safe space,” we were told. The much-awaited conversation was supposed to let us compare our practices and widen our understanding of what “welcoming’ means, but before it could even begin, we were served notice that the circle was too narrow and that some people were excluded. No conversation took place.

To be sure, most participants — artists, volunteers, spectators — loved their experience at the festival for all the right reasons. Many collaborations, partnerships and friendships emerged from FAAS 6. The festival also hosted preparatory work for the residency of three Franco-Ontarian artists, Pascaline Knight, Mariana Lafrance and Julie Lassonde, who were part of “Manifeste,” a multidisciplinary project that aimed to underscore through artistic creation the upcoming construction of Place des Arts de Sudbury (soon to open, as these lines are being written). Together, the three artists created a series of installations and performances entitled “Viens” (Come), which was presented at the GNO in the winter of 2019. “Come,” as in welcome, as in invitation, openness, sharing a space, a territory. Questions about sense of place were everywhere in October of 2018.

The names for Sudbury and the surrounding area are different in different languages. In Anishinaabemowin, the place where I am writing these lines is called N’Swakamok, “where the three roads meet.” Francophones, for their part, coined the term Nouvel-Ontario, echoing the term New-Ontario, to refer to a symbolic or even mythical place where Franco-Ontarian culture and identity find expression. In collective imagery, it represents a shared space that is distinct among the other Francospheres of Canada. A word, and an opportunity to dream. Every Northern Ontario poet I know has written a poem on Sudbury’s infamous black rock and slag, on stands of twisted spruce; it’s practically mandatory. But fifty years after artists laid claim to this term, notably by using it to name their institutions, how does that spirit of reappropriation measure up against the dawning of a worldwide movement towards decolonization? That, too, was a topic we had hoped to discuss. The GNO is a Francophone organization, but the art it exhibits isn’t fraught with linguistic divisions and the organization’s documents (such as this publication) are bilingual. Nonetheless, in everyday settings, the organization’s language of work is French. So, it is not representative of other linguistic communities, even when they are diligently consulted. Representativeness, representation… there was never any question of speaking ‘on behalf of’ anyone. However, despite our best intentions, perhaps we were not the organization best positioned to raise the question ― theoretical for some, personal and difficult for others ― that served as the theme statement for the FAAS: “For whom?”

Despite the tensions, the FAAS went forward. We were thrilled, and somewhat relieved, to host the Saturday evening performance event that concluded the programming. The Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague building was alive with music, declarations, video projections and lighting features put together by the artists. Time flew as performances came one after another, concluding with John Deneuve’s presentation on the stage of the former school’s amphitheatre, located in the basement. Deneuve, who lives and works in Marseilles, brings together on stage festive balloons, a children’s toy house made of plastic, an American flag, big inflatable swimming pool animals, a Christmas tree and other accessories. On a screen at the back of the stage, a video shows images from a retro-style home deformed by funhouse mirror effects and synthetic, psychedelic colorization. Colour-changing spotlights sweep across the stage and the audience under the blare of techno music that Deneuve controls from a console that is on stage as well. Hidden under a blonde wig, the artist is everywhere at once. She runs across the stage, stumbles over toys, flounders, rides the giant plastic duck. Microphone in hand, she hoots enthusiastically — ooh! ah! — and uses rubber accessories to produce sounds which are, like her voice, subjected to a number of distortion effects. She jumps down from the stage, slices through the crowd, flings herself back among the balloons. Her costume slips, her clothes fall by the wayside piece by piece and she continues to perform, with seemingly inexhaustible energy.

There is something childlike in this universe of disorderly movement, excessiveness and overabundant decibels: a joyful, almost voluptuous atmosphere stems from this performance which conveys a deep sense of freedom. Deneuve goes back into childhood, working counter to adult logic and equilibrium. She performs with willful impropriety as she pulls out a tail from under her dress and lets it hang between her legs, or when she frenetically rides inflatable toys as if in sexual intercourse. Within the four walls of her little plastic house, she is Alice high on mushrooms, her body too large for her ambitions, for her toys. The mayhem is absurd. The artist is having fun. The wig, the sequins, the plastic, the garish colours, the heady techno beat, all these elements emphasize the artificiality of this representation. Even the video, and the rituals of conjugal life it presents, indicates through the distortion of the images that reality has been manipulated and choreographed. Nothing is real and everything explodes in Deneuve’s universe. And it’s all for the best, as this work gives rise to a feeling of joyful catharsis.

One could not have hoped for a better closing performance for the FAAS. The energy is contagious. The spectators are in a festive mood. Now, it’s time to dance… And so it was with aching feet and eyes still heavy with sleep that we arrived on Sunday morning for a final tour of the installations before tearing everything down. The artists are leaving, the team stays behind. It’s time to clean up, empty the space, bring back borrowed items and return this loaned space to its original state.

For four days, École Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague School was the GNO’s beating heart. But as we leave, there are many more questions than answers, along with a deep fatigue twisting through our bones. Part of it is that the weather is cold with heavy wet snow that sticks to the soles. And like that snow, my thoughts are heavy as I revisit the memory of the FAAS some three years later. In spite of the achievements, the adrenaline, the unique event I’ve experienced, I’m still thinking that we could have done things differently; that I should have known, foreseen, worked harder; that technical glitches, leaky roofs and heartaches may well remind us that we’re human and therefore fallible, but should not allow us to forget that we can always do better. “This is not a safe space.” An open door is not enough. There are all sorts of reasons for not wanting to enter. The walls need to come down. The light needs to get in. Taking time. Consulting, again and again, but also becoming involved in the projects of others in order to learn how to work, to think and to create differently. Decolonizing our ways of doing. To bring about a paradigm shift. Between the walls of Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague, I learned that goodwill isn’t enough; that without foregoing joy, discovery, wonder and fun, privileges must be recognized and discomforted, even when it’s unpleasant, even when your nose gets rubbed in your missteps and mistakes. I learned that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to the issue of sharing territory.

I still have much to learn. But on the strength of my experience at the FAAS, I hope to become, some day, a person-place by whom everyone feels heard, so that the conversation may move forward.

—Chloé Leduc-Bélanger, former Communications and Development Officer, in collaboration with Danielle Tremblay

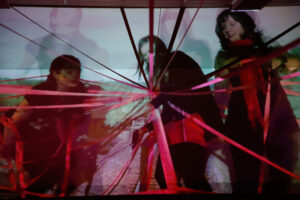

Jean Ambroise Vesac & Jules Boissière, 2018.

Deanna Nebenionquit

The Intersections of Territory

The Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague elementary school sat across the street from my high school. During my four years as a student, the red brick building remained vacant. Over time I wondered what the interior looked like, and whether its old bones were strong enough to host something worthy of its long history. The two-storey building had managed to fade out as another dead space in the downtown Sudbury landscape, and I forgot about it when I graduated.

Over ten years later, the folks at the Galerie du Nouvel-Ontario (GNO) saw the building’s potential and for one weekend in October of 2018, transformed the decrepit space into a funhouse. Artists descended to explore the concept of territory, and to visualize what that term meant to them as a settler or visiting kin.

As a member of Atikamkesheng Anishinabek, this region is quite literally my territory in every sense of the word, so I was curious to see how others would interpret the theme. I started my FAAS journey where any reasonable person would, deep in the bowels of the building. The artists occupying that space used a wide variety of media—found rocks, sticky notes, archives, intricate lighting, and food—to illustrate what territory meant to them. Masking-tape lines zigzagged across the floors, and I motored along with them like a game of hopscotch leading me to a corner of the room filled with dried foliage, moody lighting, and inviting smells of tea and baking. As I walked through a makeshift doorway, I immediately recognized the ambiance of an Indigenous space. Debajehmujig Creation Centre, based in Mnidoo Mnis, has been transforming spaces since 1984. In this particular space, people were talking and laughing, huddled around tea and bannock. The immersive installation mimicked the bush, and thus a teaching space. The Seven Grandfather teachings were inscribed on wood and hung from white birch branches. Some of the terminology was different from what I’ve been taught; we discussed that even though we are Three Fires kin, territory and distance can make us distinct.

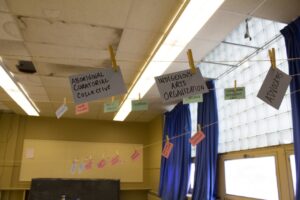

I knew the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective (now called the Indigenous Curatorial Collective) was somewhere in the building, so I decided to seek them out. Inside a classic elementary schoolroom, I found several obstacles made of yarn and notes strung up from one wall to the next like a giant spider web. A formal business table was set in the middle of the space, where serious-looking individuals were seated. The energy was the exact opposite of what was being transmitted in the basement I had just visited. The people were working hard on various projects with their heads down. One person was beading, a second was typing furiously on their laptop, and another was reading. I felt like it was rude to disturb them. Making my way through the obstacles of yarn towards the table, I read a few notes that were strung up on the yarn spiderwebs. The notes set the tone for the installation and, to me, described administrative burnout with a hint of frustration. When I arrived at the table I was met by a line on the floor fashioned out of masking tape to represent a wall, and a small sign that read “knock” at the entrance. I yelled an obnoxious “KNOCK KNOCK!” and waited for permission to enter the space. Context: at this moment in time, I had been out of the museum and art gallery sector for a few months, but I recognized the tension in the room as that of overworked arts administrators. While I was getting flashbacks of work-related stress and anxiety, I tried to understand why the ACC decided to contribute an installation that highlighted the inner workings of an arts institution. At that moment in time, the context of territory for the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective was transitional and vast. The webbing of ideas, tangled in notes and dreams, was a regrouping project. The resulting installation was a physical visualization of dreaming a future for Indigenous, Inuit, and Métis curators, which I presume is a daunting and stressful task.

N’Swakamok (Sudbury) is one of the main intersections in Northern Ontario, a place where many paths converge. It is recognized by Indigenous groups and settlers alike as a place where people have gathered for commerce, and where important political negotiations relating to the land occurred The word N’Swakamok means “crossroads.” The multitude of waterways that flow through this region can bring you north to the muskeg, south to the Great Lakes, and east or west with ease. When settlers arrived and mining activities began, the crossroads took on new meaning with the advent of the railway and later highways. Many of the interior waterways, such as Junction Creek, are now hidden below infrastructure while the tracks and infamous roads make up the main creases of the city. The collective Myths and Mirrors (Cora-Rae Silk and Laurie McGauley) highlighted this territory’s history of hosting delegations and deliberations by featuring the 1850 Robinson-Huron Treaty Annuity Case court proceedings [1] taking place in Sudbury at the same time as the FAAS. This particular court case was unique because it was the first Supreme Court case trial to be filmed, live-streamed, and archived for public use [2]. I’d like to say chi miigwetch to both artists for using the FAAS 6 platform to highlight territory as a modern and site-specific intersection between land, Indigenous peoples, settlers, and government.

In a way, the old run-down building represents the territory on which it stands. It is a massive, impressive structure that many want to explore and preserve because it has so many interpretations of value. Some see value in the building itself, others see the land beneath it, and some see its historical heritage. In many ways it is beyond repair: it is dilapidated, there are water leaks, the water is not fit for human consumption. While the infrastructure may be depreciated, the cultural integrity of this building lives on by those who use it as a space to learn, teach, and share.

[1] On December 21, 2018, the Court ruled that the Crown has an obligation to increase the annuity paid to members of the Lake Huron Anishinaabe nation in order to reflect the economic value the Crown receives from the territory. Since 1850, the Crown has acted in a way that has seriously undermined their responsibility to honour the Treaty. The Robinson-Huron Treaty territory has generated major revenues from forestry, mining, and other resource development activities, yet annuities have not been increased since 1874.

[2] The Robinson-Huron Treaty Annuity case can be viewed on FirstTel : https://livestream.com/firsttel

—Deanna Nebenionquit

Jérôme Havre & Laura Taler, 2018.

Jean-Michel Quirion

Re-territorialization at FAAS 6

Launched in 2008 by the Galerie du Nouvel-Ontario (GNO), the Foire d’art alternatif de Sudbury / Festival of alternative arts in Sudbury (FAAS) takes place every two years in a different temporary location somewhere in the city. These often unseemly but locally familiar spaces (for example, a vacant shopping centre or a parking lot) come with practical and esthetic constraints which can inspire the participating artists, who are invited to create in-situ or site-specific works. Throughout the festival’s successive editions, installations and performances arise like intrusions in the city, inciting the deconstruction and reconstruction of unexpected places. During these festivals, over the years, Sudbury’s public spaces become associated with democratized and shared exchanges between citizens, in what is truly a process of re-territorialization.

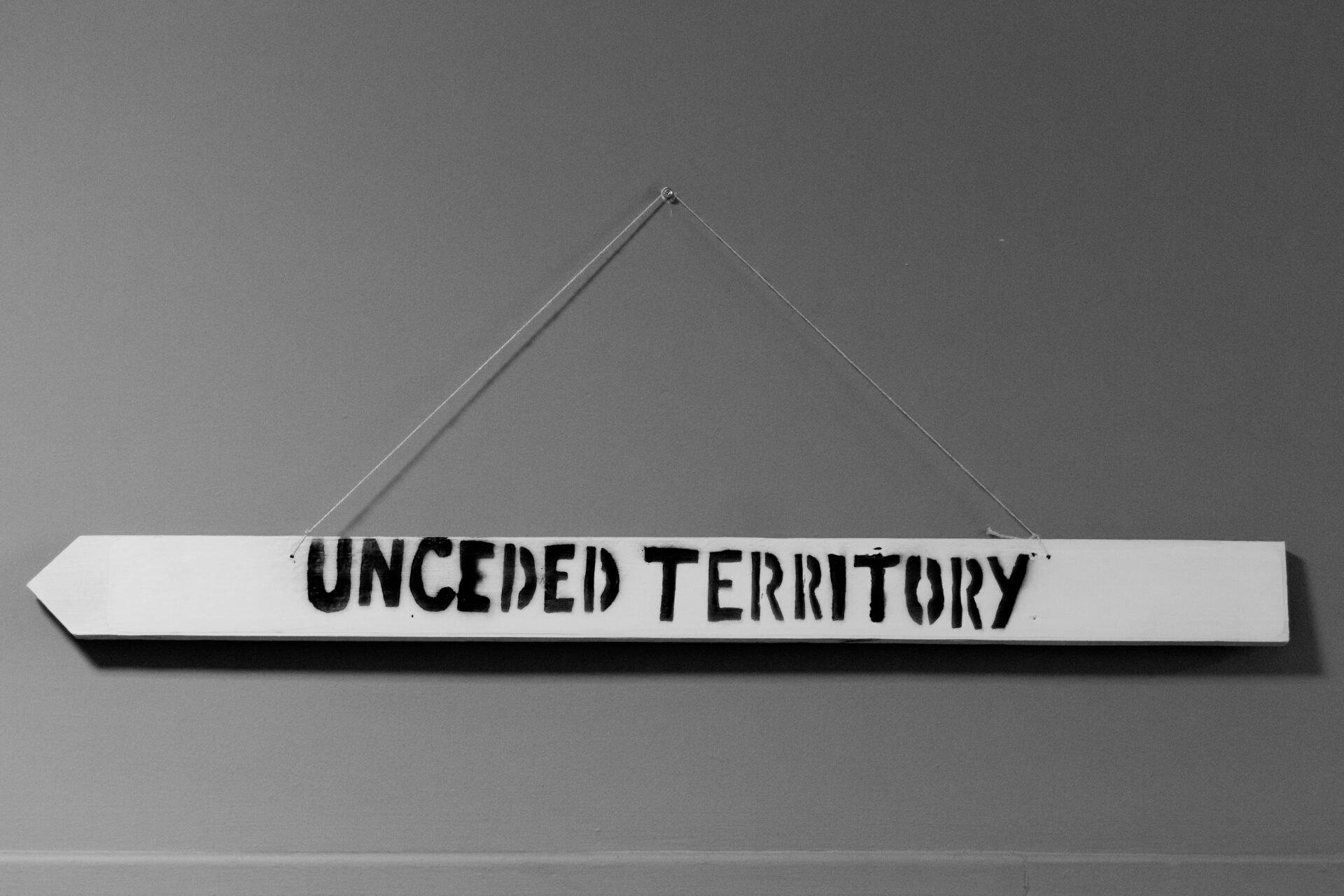

For the sixth iteration of the FAAS, presented in October 2018, invited artists roamed and surveyed the polysemic notion of territory, and in particular the question of appropriation of territory: À qui? (To whom?) Who has the right? Whose territory is it? What territory? This virulently usurped, extorted, unceded territory; this conceptualized, organized, dominated space. The guiltiness of a civilization, the legitimacy of belonging to minority groups and the recognition of ancestral territory certainly are current issues. The pages of history read like a palimpsest of stigmata, describing unjustifiable enslavement, exterminatory fury, totalitarian terror, as if the world were a concentration camp. This painful history, with its strata of geo-historical and socio-political lesions, is our story, your story.

Territory, as Maryvonne Le Berre (1995) states, can be defined as a portion of the earth’s surface that has been appropriated by a social group [1]. Therefore, territory stems from the actions of humans and is the focus of competing and divergent powers. It finds its legitimacy in the cartographical, geographical, historical and political representations it generates. The delineation of territories as practiced in the past by Indigenous peoples is generally more natural than the delineation that stems from colonial interpretations. Libby Chisolm and Molly Malone (2016) state that the legal framework in which territories are defined nowadays is based on recognizing geographic areas that have been divided by major political units, such as provinces [2]. Before Canada was colonized, the concept of nation-state as it appears in Western political science did not exist among Indigenous peoples. Each nation had its own political structure, which varied according to the cultural history of the area – and the nation involved. In a sense, settlers imposed upon Indigenous communities the concept of nation-state, along with the various dominant notions of territory which stem from that concept [3].

In what used to be Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague elementary school, now a vacant building at 162 Mackenzie Street, on the territory of the Atikameksheng Anishnawbek nation, artists made use of every classroom to explore some of the ramifications of our colonial history. The thirty or so participants invited by the GNO, including artist-run centres and Canadian organizations involved with themes of territory, appropriated the school in order to use it as a place of pacification, not subject to any decision-making authority. The diversity of its guests provided an opportunity to bring about a necessary redefinition of what a space open to today’s – and yesterday’s – social realities should be. However, such realities are never historically neutral. They are composed of different visions that meet, mix and collide. In a wide-ranging survey of the notion of territory, marking their way with demonstrations, protests and artistic encounters that led – or did not lead – to consensus, participants strove towards integration and conciliation of territories for all, resulting in a momentary emancipation from the wounds inflicted on society – on identity – in the past. The building temporarily became a sort of non-space, devoid of the usual waymarks, a shared borderless territory, a zone beyond nations. For once, during FAAS 6, territorial limits ceased to be.

Spiritual territory: invocations interred

Isolated in a storage space filled with stones and soil collected outside the building on a nearby worksite, Terrance Houle (Calgary, Alberta), an artist of Kainai (Blood tribe) ancestry, presented Song for Fallen Mountain (2018), from the processual series Ghost Days. Reflecting the beliefs of his nation, he performed a sort of ritual that used the building’s static resonance as animate matter, as well as the energy of spirits which might dwell there. The strident and somewhat disturbing sounds the artist brought forth from his theremin were like lamentations, as if he was attempting to summon the great beyond. In continuity with Houle’s practice, which often involves interventions on sites dedicated to sacrifices, this performance embodied the silences suspended in this place and brought buried memories back to life.

Interior territories: memories interred

John Court, a performance artist originally from Great Britain who now resides in Tornio, Finland, was invited by the FADO Performance Art Centre (Toronto, Ontario). Being dyslexic, the artist dropped out of school because he struggled to read or write and his relationship with communication and education continues to be conflicted. So for him, a school building would be a place of linguistic alienation. The classroom he chose had wide blackboards, and pieces of them (the ledges that held the chalk) were lying on the worn floor. During the preliminary work for his performance, Court planned out the challenging, intensive, obsessive execution of a sequence of actions repeated over a long period of time. Wordlessly, the performance denounced the pain he experienced in learning and aimed to express the consequences of poor access to specialized education, among them his (self)-isolation due to his inability to understand language. The series of actions performed by the artist consisted in endlessly rotating, with one of long blackboard ledges perched on his shoulder, and also circling the edges of the room while leaving chalk marks on blackboards and walls, all the while maintaining the precarious balance of his burden. Despite his agility in executing the movements, the performer displayed an attitude of weariness that made him seem somewhat detached from the obligation of pressing on with the performance, that is, to rotate, to keep the burden in balance and to mark the blackboard with countless chalk marks. Considering the process of bodily adaptation inherent in complex actions, one may reflect on the personal conditions in which the ability to perform actions such as these can develop. Gradually fatigued, and then exhausted, after more than four hours of incessant wavering, the performer gave up and left the room. By using an educational institution as his setting, Court was able to challenge the structures of language learning, which for him have always imposed a form of servitude. During his performance, some spectators would venture into the classroom space, creating palpable tension. A classroom was thus transformed into its antithesis, a space contrary to the conventions of teaching and knowing.

Rah Eleh (Toronto, Ontario), a Canadian of Iranian origin invited by the GNO, presented The/Da (2018), an intense choreographic proposition infused with her experiences as an immigrant and her forced adaptation to the ideologies of Canada’s dominant language, English. Plural sensitivities emerged in this intimate and confrontational work that had at its core an experience of personal restriction. The choreography consisted of a series of fluid movements following one another in a controlled improvisation. Simultaneously simple and difficult, painstaking and disarticulated, the coordinated movements involved torsions of the limbs never leading to a moment of culmination. Through her gestures, Ran Eleh denounced practices of literacy training used on immigrant children. Her actions harkened back to her early days in Canada, when a teacher at school would squeeze her mouth to try to get her to correctly pronounce the word “the.” To recall the stigma of harsh integration, the artist inflicted the same incisive gesture on herself, lowering her jaw and repeating “the – da,” and she prolonged the choreography to the point of exceeding the limits of her body. In Eleh’s performance, the gesture of dancing became a form of advocacy and, remarkably, it conveyed language through action.

Speaking to diasporic realities as well, Jérôme Havre, a Canadian artist born in Paris, France, erected two architectural and vernacular representations favouring the immersive dimension, in the GNO’s gallery space as well as the FAAS’ venue. At the GNO, the exhibition was entitled Intérieur ou Comment les mots viennent quand les formes jaillissent de l’intérieur? (Interior, or How do words come when forms come from within?) and the work was a window into the artist’s universe, or at least a fraction of it. In the middle of the gallery stood a huge structure shaped like a hut, built of clay mixed with straw using a ‘wattle and daub’ technique called torchis in French. On this structure, Havre conspicuously traced opulent symmetrical designs. The installation explored the concept of sovereignty – over a territory and over oneself – through the bilateral notion of welcoming and occupying. Conversely, Havre’s work presented in the FAAS venue brought viewers into a totally different universe, which was a dreamlike space. Entitled Relaxing White Sound (2018), this work represented abstract phenomena, like the farthest reaches and unknowable dimensions of the universe, in the form of a slender stairway rising above a large basin full of water and crossing through celestial movements under a nighttime sun. This installation invited spectators to traverse the artist’s imaginings and question unexplained phenomena, such as the limit states of matter.

Laura Taler (Ottawa, Ontario), a Canadian artist of Romanian origin invited by the GNO, screened her video work Carry Tiger to the Mountain (2017), in which she uses the slow movements of her body to negotiate with the territory that surrounds her. Projected on textile in the school’s basement, this soothing video shows a serene Taler moving on the shore of the Atlantic. Meditative, repetitive gestures with a spiritual dimension embody a landscape, endow it with flesh. The movements adopt the logic of dialogue, through gradual and reciprocal exchanges between artist and territory. These exchanges ultimately constitute Taler’s choreography of a landscape.

Exterior territory: capturing a metanarrative

The image of a human calculator is an apt description of the stance held by Geneviève Massé (Montréal, Québec), because for the duration of the fair, she became a generator of all sorts of data. Presented by DARE-DARE (Montréal, Québec), this artist’s conceptualization of territory was based on survey codes, systemization principles and documentation techniques, which she used to probe Sudbury by tallying all sorts of elements that make up the school building and neighbouring streets. Massé converted a classroom into a counting office in which she produced account statements which were exhaustive and intensive, considering that she had only a few days to complete her disproportionate project. Through her attentive presence to the territory, in her wanderings and observations in different places and her engagement with citizens in order to elicit collaboration adapted to the territory targeted by her intervention, she captured spatiotemporal data and transcribed them in written or in graphic form. This empirical process, which takes both qualitative and quantitative aspects into account, allowed the artist to count, list and classify tallied elements in the form of cartographic and geographic metanarratives. With unfailing diligence, Massé wrote in and crossed out more and more graphic and written proof of her tallying on the classroom’s blackboards.

Territory: À qui? (To whom?)

Aside from the creative programming, the festival also included a round table discussion on the notion of territory entitled À qui de droit? ― a phrase that usually means “To whom it may concern?”, but in this context could be understood as “Rightfully whose?” ― with participants Elia Eliev (Ottawa, Ontario), Jinny Yu (Ottawa, Ontario), Camille Larivée (Tiohtià:ke/Montréal, Québec), Mariana Lafrance (Sudbury, Ontario) and facilitator Kai Wood Mah (Sudbury, Ontario). It provided an opportunity for mediation and careful reflection on the collective and individual sensitivities of the participants and the public. However, the polyphonic conversations that ensued were unsettled, due to divergent views among the panelists and public. Most of the comments discussed the ideological structures of colonial power that remain in place today in many institutions. The discussions provided an opportunity to become aware of our own position on this territory. To speak of something, one speaks from somewhere.

The works presented during FAAS 6 were evidence of the links forged between the fields of expertise, and also the personal qualities, of the artists who were present in this place and this event’s invitation to plurality. To whom? Rightfully whose? Whose territory? What territory? A plural territory. Re-territorialization, somewhere, differently, in Sudbury. A territory with its own trajectory: prospection, occupation, interaction, comprehension and emancipation. Free from totalitarian legacies, the artists took possession of this (un)limited territory, or at least a part of its expanse. This territory is inalienable and impartial: it is a thinking-place. It is sensorial and indeterminate, yet real. Together, the artists rewrote the pages of a history which is no longer about domination, but rather the promotion of free expression and demonstration.

[1] Le Berre, M. (1995). “Territoires“ ». In Bailly, A., Ferras, R., and Pumain, D. (ed.). Encyclopédie de géographie, Paris, France : Economica.

[2] Malone, M. and Chisholm, L. (2016). “Indigenous Territory“. In The Canadian Encyclopedia, July 5, 2016, Historica Canada. Retrieved at https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/indigenous-territory.. Retreived July 2, 2020.

[3] Ibid.

—Jean-Michel Quirion

Installation, Laura Taler, 2018.

Thierry B. Gateau

Territory between fixity and movement

The sixth edition of the Festival of Alternative Arts in Sudbury (FAAS) had territory as its theme and, for its theme statement, the French words À qui? (To whom?), which echo the Anishinaabemowin word aki, meaning land, as both matter (soil) and place. The intellectual gateway to the 2018 biennale is thus the notion of property, of belonging. In a well-chosen venue, the vacant Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague school, this year’s FAAS invites artists to symbolically and physically take ownership of an abandoned educational facility, a non-place, and transform it into a place of reflection and discussion on the issue of territory. At the heart of the event is the will to engage in dialogue on the colonial roots of the very notion of territorial appropriation in modern Western languages. À qui? immerses us in a variety of approaches, actions and representations that leave no one indifferent. In our encounters with the artists’ works, two general interpretative categories emerged: territory as fixity and territory as movement.

Territory as fixity is circumscribed. It is a known place, but can appear under various forms. This is territory as isolation and solitude. Here we observe two contrasting variations. A first form is confinement and detention. As a closed space, as forced claustration, it represents a threat to those who are within it. One is subjected to social and political pressures, to physical and psychological imprisonment. That is what we encounter in the works of Ruth Belinga, Serge Olivier Fokoua, Michel Bitimbe and Rah Eleh. But confinement also appears as a retreat, a shelter. This is isolation in comfort and security, protected from threats. À qui in French sounds like aqui (here) in Spanish and ‘here’ is where we have come to collect our thoughts, to experience the intimacy of the space, its objects and occupants, to gather and to meet, because we’ve been invited. That is what transpires from the meditative performance of John Court, the intimate performance of Terrance Houle and the participatory installations of the Debajehmujig collective, Anyse Ducharme or Patrick Harrop.

Territory as movement is ever-changing. It is defined and constructed through action. It is perceived through dislocation and relocation. It can be the territory of migration and nomadism, but also of travel and discovery. Migration can be either forced or willing movement. Nomadism is a way of life. The conditions that compel people to move elsewhere are often those of discomfort. The works of Martin Beauregard and Joseph Muscat are illustrations of that state. The works of Jean-Ambroise Vesac and of Jules Boissière focus on migration in the digital world. Attraction, curiosity and the desire to know are also conditions that compel people to move elsewhere. Exploration is an expression of that spirit of openness. Observing, studying, analyzing, learning and meeting are also forms of movement towards the Other and the beginning of knowing. The collective Les Poulpes recounts a trip. Other artists, such as the duo of Mathieu Boucher Coté and Marika Drolet-Ferguson, as well as Geneviève Massé and Yanie Porlier, each in their own way, draw inspiration from their extramural wanderings in the city of Sudbury and offer the fruits of their explorations: sometimes the emotions, sometimes the things, sometimes the fragments of a story.

Confinement/Threat

“The world’s problems are more cultural than they are political.”

Music tinged with tropical and New-Age influences is heard above a noisy background produced by two fans. The wind they make agitates liquid-filled condoms suspended from the ceiling with nylon threads. It is a forest of colourful phalluses.

The artist performs in a satiny black velvet dress with lace trimmings. Her face is painted white. Ruth Belinga evolves in an ongoing dance through the forest, bumping against the condom trees, which sway and bounce back. At times, her dance is interrupted, as she pierces some of the condoms with a syringe and ingests their milky content. Many of the hanging threads become intertwined over the course of the dance.

At times during her performance, Ruth Belinga draws spectators into her forest and makes them read short statements that aim to have them embody the presence of a tree. Once a text has been delivered, Belinga asks the participant to hand the text over to someone else who, in turn, joins the metaphorical forest.

The tree is an idea drawn from Scandinavian imagery that has inspired the artist. The forest of suspended condoms represents phalluses, symbolizing male dominance. Woman, the nymph in the forest, moves through her setting, her realm.

The Cameroonian performer touches on the concept of territory and deforestation as a metaphor for domination over the female body, illustrated by hanging condoms filled with paint that form a phallic forest in which the woman is imprisoned.

Serge Olivier Fokoua positions himself between three support columns in the school’s basement. He has wrapped them in painted blue paper. In the middle of this triangle, he has placed a wooden pallet. A small vibrating motor sits on the pallet.

The performance begins when the artist turns on the motor, which emits a continuous drone. Wearing a blindfold, a wig and a blinking headlamp, he moves forward, holding a huge roll of transparent industrial adhesive tape. In a wide circular movement, he blindly wraps the tape around the columns, brushing against the spectators assembled around the structure. The performance results in the creation of transparent walls between the columns as the artist circles around them. The ‘windows’ thus created enclose the light emitted by blue and pink LEDs that feebly illuminate the space.

The sounds of the motor and the tape unwinding add to the paradoxical effect of confinement within transparency. The blind performer repeats his trajectory, clinging to his adhesive tape like a guiding thread. He is dependent on his circular trajectory. Perpetual motion, blindness and transparency speak to existential alienation.

Confinement in structure, confinement in movement; now Michel Bitimbe presents us with confinement in language: the language of political discourse. In his video performance, he obsessively repeats the French words for ‘sardine’ and ‘bread.’ As the video progresses, the frame narrows in on the artist as he performs in a setting that might be a Cameroonian market. The spectator is drawn nearer and enters the frame, the scene, the landscape. A montage of cuts and repetitions produces an effect that borders on hypnosis.

The artist repeats: “The sardine. The bread. Seven years. The sardine. The bread. Seven years. The sardine. The bread. Seven years.” With humorous sarcasm, this video criticizes the regime of Paul Biya and the RDPC party which has governed Cameroun for over 36 years. The party was re-elected on October 7, 2018, a few weeks before the artist’s residency, after having promised that throughout its term of office, there would be daily distributions of free bread and sardines. This is that government’s recurring electoral discourse, the basis on which it constantly gets re-elected. Cameroon’s population is experiencing a social crisis due to generalized extreme poverty and a corrupt government that maintains an ambiguous post-colonial relationship with France. The famished people literally throw themselves on the loaves and cans thrown into the crowd. With circumspection and disillusionment, Michel Bitimbe denounces the result of the recent elections in his country. It should be noted that this artist participated by remote video performance because he was not allowed to leave his country to be a part of the FAAS in person.

Rah Eleh offered a choreographed performance based on autobiographical aspects of her immigration experience.

At age five, as a refugee from Iran, she struggled to correctly pronounce the sound ‘the.’ Her Canadian teachers punished her and tried to get her to pronounce sounds correctly by using their hands to force her mouth to move differently. She had to stand in the corner and copy lines on the blackboard. From this traumatizing experience came the inspiration for her performance presented in a very relevant setting: a classroom in an elementary school.

The sounds Da – Tah – The (2018). They are the three phases of learning, of integration, of assimilation through the constraints of language; the three phases of the evolution of her accent in pronouncing those sounds.

Moving from a central point in the classroom, she traces two diagonal lines towards each end of the blackboard on which the copy exercise was written. Da – Tah – The . The centre represents stability, the dominant institutions, the Western norm. The extremities represent marginality, difference, foreignness. In the middle of these lines, the choreography is active, with much agitation expressing tension. Doubt, pulling away from stability. The transformation from Da to The goes through Tah.

Rah Eleh proposes an exploration of language and movement. The choreographic gesture, like an extended arm, connects the margins, the abandoned, the oppressed. The centre point of her choreography symbolizes Western dominance and normalcy. She expresses the tension between the peripheral foreign space and the expectation of conformity, searching for a synthesis in her mixed identity as a refugee.

The performance takes places in silence, under harsh lighting in an empty space. The finale consists of white noise representing the institutions. The performer exerts pressure on her mouth, as did the teachers that forced her to transform her pronunciation. Transfigured, she howls: “The!”

Retreat/Security

From the start of the residency right up to his performance, John Court is present on site, feeling the pulse, sensing the energy. He quickly settles into his allotted room. In an empty space under harsh light, he places long pieces of wood that are almost beams. The atmosphere is bare.

John Court makes use of what’s in the room: four lengths of wood, bits of chalk. His process is simply being present, staying in tension with the objects, always having them in mind. His intention is to execute a performance that develops slowly, over many hours if his body allows, rather than a showy spectacle. The action is based on concentration. It’s his way to give a profound answer to the question of physicality: one must be in reality, with reality.

During the first days of his residency, the artist gets his bearings, hangs around in the building and near his pile of wood. He contemplates the objects. Meanwhile, he is very sociable and often talking with artists, organizers and onlookers who are wandering around the school building. All of a sudden, he changes the position of his planks. Is it a solution? An answer? He is gauging the problem. On the eve of his performance, he becomes more solitary and enters into an introspective phase.

As his performance is about to begin, John Court has chosen his pieces of wood, which are now positioned according to a relation with the environment that he finally determined in the days preceding. His action consists in lifting big long pieces of wood and balancing them on his shoulder. The floor is littered with pieces of chalk. Chalk scribbles, which he scrawls throughout his performance, mark the blackboards in his classroom.

It’s an evocation of Calvary. John Court bears his cross. He pivots in place, holding a steady gaze, in equilibrium and in unity. Seemingly under constraint, Court enters into a sort of pacified trance, in unity with his material, his space and his body. It’s an almost mystical experience. The body becomes a part of the environment in a dance that is hard, yet serene.

When imbalance wins out, the pieces of wood fall loudly to the floor, which is cluttered with other planks. The heavy noise resonates all the way down to the building’s basement.

Terrance Houle is cloistered in his cramped space, a compartment in the basement of the Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague school building. It’s a small angled room in a subterranean stairwell. Several steps covered with rocks lead to a condemned door. His instrument, the theremin, lies on a bed of earth, plugged into a mini-amplifier with a loop pedal. The theremin emits long, delicate sounds. The player’s hands modulate the sound wave by hovering near the instrument’s antennas, thereby varying the sound’s pitch and volume.

In his cubbyhole, Houle is framed like a living portrait. Confined, he dances with the antennas of his theremin to produce the long eerie tones characteristic of this instrument. Facing him is a log on which we can sit, like in a booth. At the door of his cubbyhole, an antique wheelchair stands guard.

Houle is in his retreat, isolated and in peace, where he receives his visitors in small, intimate groups.

Anyse Ducharme’s approach to territory is rooted in space as well. In her work, the building is not an enclosure or a constraint, but rather the very means of exploration: the building is her instrument. Her practice of audio art is firmly architectural: it is inspired by, and generated by, the built environment. The esthetics of the installation St-Louis de Zig-Zag (2018), uncompromising and undisguised, are wires, loudspeakers, a subwoofer, piezo microphones, orange adhesive tape and doggie toys. Nothing is concealed; wires run along the walls and floors from the machine room to the upper levels of École Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague.

Contact microphones are installed on the floors, in the windows, the walls and the stairwells, on the boiler down in the basement. The artist has also set up hydrophones (contact microphones inserted and sealed within plastic doggie toys) in the drinking fountains. All these mics are accessible and the public is invited to interact with the installation by walking, talking and drinking nearby, or even touching the microphones. The sounds produced by these interactions are transmitted to the artist, who literally remixes the building in a process of self-generated composition.

From this reflective standpoint, Anyse Ducharme invites her audience to reexamine their relation with the school’s built structure, and this could lead them to a repositioning in relation to the built environment in the wider sense of the term. Here we reflect on our relationship to habitat. Self-reference and feedback: the building plays into itself.

Patrick Harrop’s work is a light box, a small space filled with a number of elements that range from transparent to reflective. The micro-movements of a metallic backdrop, or the blur created by translucent film placed on windows opening onto the hallway, create an effect of confinement. The room (formerly the secretary’s office) is small and within, it’s as if we were viewing the inside of a complex lighting system. Coloured nylon stockings stretched with fishing line are lighted by lamps and colour projectors. An open window lets in wind that stirs a large sheet of metal which acts as a reflector, producing a shimmering movement.

The artist adapts to the space, makes it his own. For this residency, he experiments with reflected light, using it here for the first time on a large scale. He takes advantage of the unexpected effect provided by the transparency of the room’s walls. He adds diaphanous paper to the windows of his small space. In his little room, he boxes in the light. The large reflector is a sheet of aluminum at which two spotlights are aimed. The mirror effect is distortive to the point of abstraction.

The central element of the installation illustrates a frozen movement, that of an atomic explosion or the Big Bang. Expansion is represented by imbrications of dark colours tending towards pale colours. An evocation of movement; an expansion of membranes. For Harrop, a building becomes dynamic thanks to the light within it. Territory is an equation between movement and space. The presented work is as refined as the art of the silversmith in the quality of its occupation of space.

Migration/Nomadism

Martin Beauregard’s work is highly contrastive. It mixes elements of cutting-edge technology with elements of inert nature. It consists of a digital animation projection, surrounded by rocks, stalks of dried plants and pieces of sun-bleached wood.

Martin Beauregard deploys his installation quickly. In a dark room with pale blue light, his screen is huge. In front of it, a pile of rocks, collected in the vicinity of the school and carried in by volunteers, creates the impression of a job site or a labour camp. The transfigured space, with its stems of wood, strands of straw and hoops of bleached wood that might be bones or driftwood, seems to set us up as shipwrecked castaways.

The video shows people in unstable, deconstructed, limping movement, illustrating the hard march of migrants. The audio is ambient sound and the images were created using video game software. The animation provides the narrative element, the story. Beauregard contrasts the narrative of migration with the fixity of the setting. In his work, the narrative is random, but not generative. It is partly determined. For its part, the natural setting is unreal. The work presents a fiction of nature in the esthetic of a video game. For the artist, territory is ecology. He questions the link between nature and migration and our relationship to nature as reality.

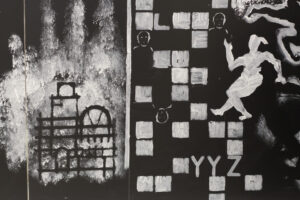

Ironically, a former teacher of colours in architecture brings to FAAS 2018 a fresco in black and white, which basically consists of various stencils. Highly influenced by its location, this work evokes chalk on blackboard. It is especially meaningful in the setting of the classroom allotted to the artist in residence.

This autobiographical work stems from a reflection on Joseph Muscat’s personal occupation of territory. In particular, he questions his own trajectory and the anonymity of migration: “Born on an island – Moved to Toronto – Studied in France – Travelled all over the world – Covered a lot of Territory.” He has entitled his work Terrhistoire/Terrhistory.

“I often feel like man from nowhere.” An element draws attention: a street, discretely visible in the work, and the letters YYZ, the airport code for Toronto. The artist is eternally uprooted, away from himself, like a nowhere man.

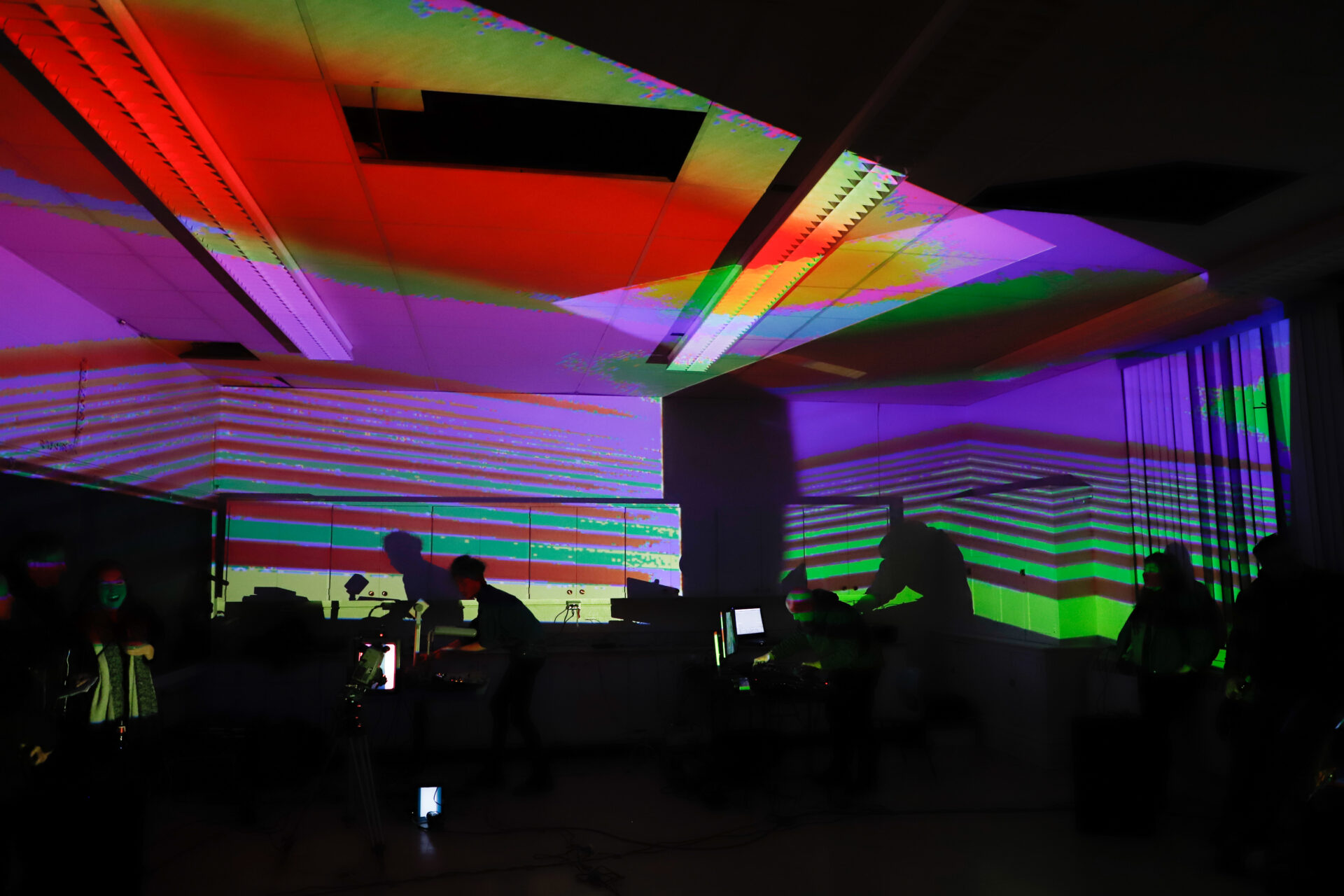

The work created by Jean-Ambroise Vesac and Jules Boissière at first gives us the impression of being in a laboratory. Their residency space consists of tables, machines and computers. During the week, they receive “patients” who play the part of test subjects for their experimentation. Initially, the process is individual, requiring a meeting between the artist and the participant.

These artists/researchers in the field of digital creation reflect upon the very process that leads to the work as a series of moments. They are interested in “digital togetherness.” Togetherness is supported by a digital culture, by virtual coexistence. Little by little, the spectator takes part in the creative process, interacts with the work and ultimately becomes an integral part of it.

Jean-Ambroise Vesac manually captures a 3D image of a volunteer’s face with a portable scanner. Then, a 3D model made of points and lines is produced. Three textures are superimposed and this produces a series of photos of the subject, which are then brushed with colours. The end result is printed and hung on the wall, thus creating a mosaic of photos of participants. While the process is underway, the work is projected on the room’s windows and blinds. Line structures appear. The form becomes decomposed.

Digital textures projected onto the walls with electronic sounds, glitches and noise make up the sound design.

In performance mode, the artists manipulate all of the elements of form and texture in an explosive action. While a repetitive electronic noise music soundtrack plays, Jean-Ambroise Vesac tinkers with a 3D portrait which pivots on a wall. A different projection lights up the ceiling. Jules Boissière operates a camera pointed towards its own images on a screen to create analog light feedback effects. Using his fingers to manipulate the image, he produces kaleidoscopic effects. As the performance draws on, the accumulation of sound, light and colour effects produced by the two performers become more saturated, stroboscopic and intense. Digital migration becomes a rite of passage.

Exploration/Discovery/Travel

Hailing from Chicoutimi, the collective Les Poulpes (French for The Octopuses) invite us into a world of assorted items they call their “install-action.” The three artists create spaces and ambiances to construct the context of their work. It could be described as a set design for a creation in which there is a performance of installations.

Their treatment of territory is to a certain extent a way of revisiting their work Convoi (2015), a series of performances held in train stations during a train-based residency across Québec, the Maritimes and Ontario. A film of this project is projected in an anteroom that serves as a boutique at the entrance of their space.

Their appropriation of the space is a sort of itinerary through which we question, explore and discover. “Octopus art shall be tentacular,” says their manifesto (in French). We enter into their rose-hued space where several modules are set up. These stations are subspaces in which actions will be performed over the course of the week and at the festival’s evening of unveilings. Their action is a continuous performance.

The stations :

A mobile made of elastics, carabiners and whistles, objects that come from the work Convoi (2015). Elastics and carabiners serve as anchor points in a relation with territory. Stationmasters’ whistles evoke a train’s departure, a moment that marks a break in a relation with territory.

A video projection of the manifesto Poulpe pour l’art tentaculaire (Octopus for Tentacular Art).

A list of things that can be done with ten dollars, serving as an opportunity to rethink the notion of value. This list will be used during a reading and improvisation on the identity of the ten dollar bill. That moment is followed by a discussion with audience members on ways of spending that amount.

A coat hanger station, which is in fact a sort of shoe tree for pink shoes, serves as the starting point for an action at the evening of performances. The shoes are mangled using wood chisels, dipped in pink paint and then worn by the artists.

A word processing station supports an improvisation on the idea of territory, in the form of a writing exercise where the artists create, using Word software six-handedly, a list of verbs that is projected live.

At another station, copy-paste and other techniques are used to generate texts read aloud and improvised by three voices using floor-standing microphones.

Octopus photos and items adorn the walls, shelves and window frames. Strips of pink crepe paper stretch out like tentacles. They bring to mind the anchor points seen in the manifesto video. The expansive network of Octopus Art has been woven. Spectators thereby have the opportunity to immerse themselves fully in the Poulpe universe.

Upon entering Mathieu and Marika’s space, visitors are invited to fill out a questionnaire. They are handed a map of the city of Sudbury, on which they are asked to situate nine emotions geographically.

The work is an exploration of a territory, a “sensitive cartography.” Quotations are scattered on the walls. The participants’ maps are pinned to a bulletin board.

Over the course of the week, the artists collect and compile the data obtained from the questionnaires. The duo compiles about thirty maps. The analysis of the data obtained through their study takes form as a single map that summarizes their research.

Mathieu and Marika offer an essay on affective memory, history and the perception of temporality. For them, the map is an affective interpretation of territory. Every card is a personal account; by isolating one parameter (the emotions), it becomes a layer of sensitivity.

This “sensitive cartography” can identify emotions in the city, depict routes and explore the visitors’ experienced emotions and their travels in their urban environment.

Geneviève Massé presents I count (2018). This project follows iCode (2013-2017), which focused on dematerialization: the artist sought to represent a digital space in the form of a physical space by producing coded images in concrete ways. For that project, she coded an image every day, representing the space occupied by binary code when it is transposed onto a physical medium, such as a sheet of paper. For her master’s thesis, she used random screenshots to create iSleep (2015), an application that recorded her sleep. With I count, Geneviève Massé’s relationship with materiality is radically different. The coder’s practice has moved into the realm of analog.

In order to return to non-virtual reality and emerge from her digital journey, the artist counts items, handles matter and objects. Her reflection touches on the human dimension of statistics and the right to be wrong. She carefully counts items in many areas of the city as a way to discover and to make an account of the territory. Her documentation also leads her to reflect on our subjective relationship with various classification systems.

Geneviève Massé offers bookkeeping services and has worked in a library, so, counting is part of her life. For her, it has a meditative aspect. Her act of counting is concentrated and calm, but in her esthetic choices, she seeks to extend the boundaries of counting.

She has chosen as her space a former math classroom. The blackboard, the old computers, the filing cabinets have the look of a bookkeeper’s office.

The form of the work is the sum of all of the artist’s research and counting: sheets listing numbers and different types of enumeration are posted on bulletin boards and categorized by day of research. As well, there are many drawings and graphics, a tally by chalk lines and trains counted in the form of paper train cars, unrolled to represent trains in motion. She even counted a large pile of rocks on the festival site. She lives a life of numbers.

Yanie Porlier sees her residency at the FAAS as a unique opportunity to conduct experiments and tests, as well as an exploration exercise. Her intention is to be open to the city and wander around historic locations and contemporary places.

On the first day of her residency, she’s off to look for images, collecting photos and videos of inspiring places in Sudbury. She is particularly attracted to the local mines. She seeks out and records sounds that are anchored in these places. To a certain extent, her process is the result of equating images, sounds and history.

There is a historical dimension to her process, as her work also includes images from archives and photos of people which contrast the present with the past, or truth with fiction.

On screen, a projector displays a mosaic of little squares, vignettes. A motion detector allows spectators to change the squares of the mosaic, which adds an interactive dimension to the work.

For this socially committed artist, art and viewer are linked through social action, and particularly the role played historically by technology in social action. Yanie Porlier’s work illuminates speech that enlightens images.

Conclusion

In this edition of the FAAS, relationships with territory found expression in fixity or in movement. The territory of stability, the reassuring place we know and appreciate, is in opposition to the territory of enclosure and confinement. Territory as movement is the territory of migration and travel. It is constructed by the decision to leave a place or to go to another place and it involves the constraints of uprooting oneself. It is also the territory of encounter.

This dual notion of territory is also in question for those who remain in place and those who receive or deal with visitors. In that perspective, the Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague school building was the territory of debates and learning that put the question of colonial relations at the heart of the happening. À qui?/aki was a creative residency conducive to careful reflection and it helped to continue an important conversation in the artistic community of Sudbury and Northern Ontario, at the confluence of Francophone, Indigenous and Anglophone communities.

Now that our relation to travel includes self-isolation and health regulations, the sharing of spaces and sensory experiences has acquired a particular new meaning. The notion of territory is renegotiated and experienced in radically different ways, most often virtually. Let us hope that our experience of human interaction will be fully revived and revitalized when we attend the next edition of the FAAS.

—Thierry B. Gateau

The authors

Chloé Leduc-Bélanger (Chloé LaDuchesse) is an author who has published in several journals and collectives. A feminist in love with words, music, boxing, she lives in Sudbury, Ontario. She is the author of Furies, a collection of poetry published by Mémoire d’encrier in 2017 which was a finalist for the Trillium Prize, and of Exosquelette.

Deanna Nebenionquit is an Anishinaabe curator from Atikameksheng Anishnawbek, formerly known as Whitefish Lake First Nation. Deanna is a graduate of the Applied Museum Studies program at Algonquin College in Ottawa, Ontario (2012) and a graduate of the RBC Aboriginal Training Program in Museum Practices at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec (2013). From 2014–2018, Deanna curated art exhibitions and managed the permanent art collection at the Art Gallery of Sudbury | Galerie d’art de Sudbury in Sudbury, Ontario. She has been working at Ontario Library Service – North as the Capacity Building Advisor since July 2018.

Jean-Michel Quirion is the director of the artist-run center AXENÉO7 located in Gatineau. Holder of a master’s degree in museology from the University of Quebec in Outaouais (UQO), he is currently a doctoral candidate in museology at the same university. As an author, he regularly contributes to specialized journals such as Ciel variable, ESPACE, esse art + opinions, Inter art actuel as well as Vie des arts. His recent curatorial projects have been shown at Galerie UQO (2018) and at L’Imagier (2020) in Gatineau and at Galerie Laroche/Joncas (2019) in Montreal. Between 2021 and 2023, he will organize exhibitions at AXENÉO7, the Carleton University Art Gallery (CUAG) in Ottawa and the Galerie d’art Desjardins (GAD) in Drummondville. Quirion has also been involved since 2016 in the CIECO research and reflection group: Collections and imperative events/The Convulsive Collections.

Thierry B. Gateau is a professor in the Management Department of ESG-UQAM. His research work revolves around creativity and organizational and social change from a human and critical perspective.